Hello Mythsters and welcome to the bi-weekly (mostly) supplemental blog. Koji here, taking lead this week to bring you some information on dragon mythology of the Southern Caucasus region: what you would know as modern Georgia, Armenia, and Azerbaijan.

I assumed that having covered Turkic, Persian, and Russian dragons, there wouldn’t be much more to the Caucasus. Of course, I was wrong. Once a mythster gets digging, one thing leads to another and a bunch of really cool myths pop up. While this area was heavily influenced by Persian and Turkic mythology, it has plenty of stories of its own. Join me as I run through some of what I learned.

Appearance

Azerbaijan Stamp

Vahagn the Dragon slayer by Austrian artist J. Rotter

In Azerbaijan mythology, the dragon is snake-like. It often has unblinking eyes, a forked tongue, the ability to move without legs, and can attack with lightning.

In Armenia, dragons are attributed with breathing fire, the eruption of blood from its eyes, darkening the sky with its breath, and creating earthquakes with its terrible roar. These features associate dragons with volcanos. Which makes sense, since the greater and lesser Masis Peaks (the Armenian name for Mount Ararat) are considered the house of dragons due to their volcanic personality.

In Georgia, dragons were a cross between a serpent and large fish with wings.

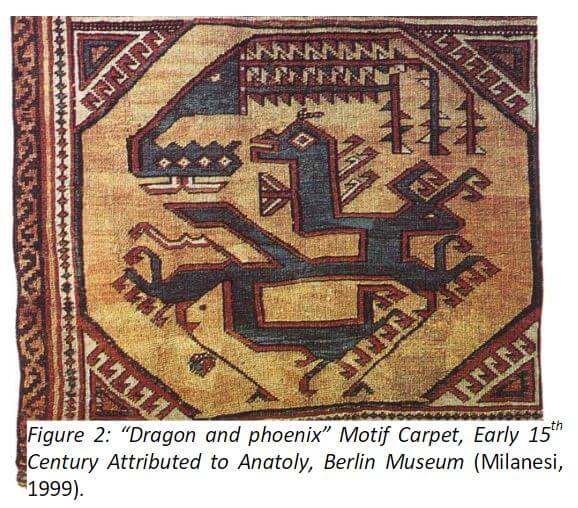

Weaving

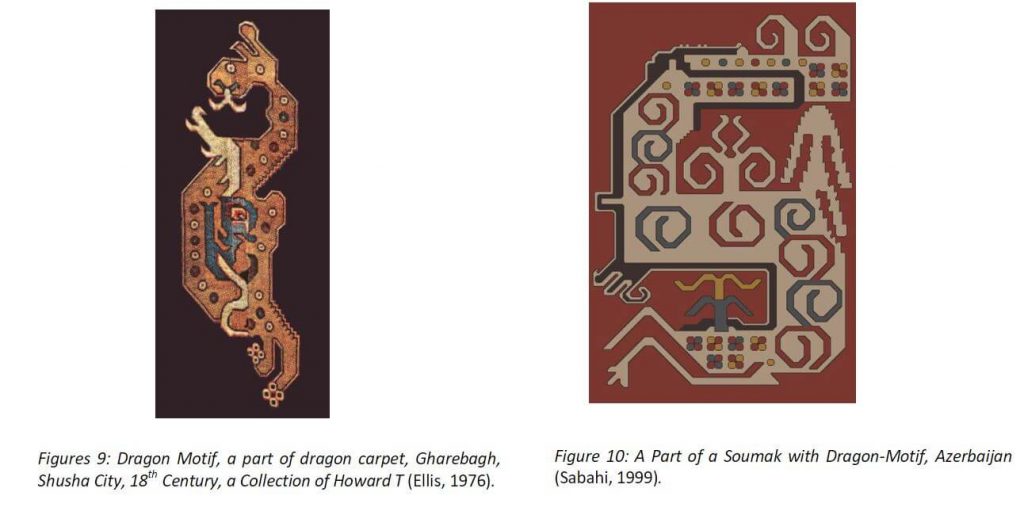

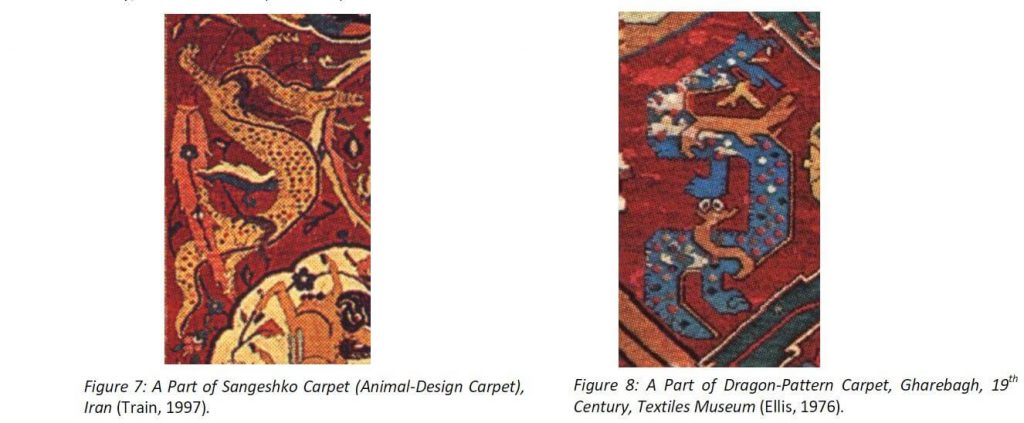

I’ve discussed dragon motifs on fabric in a few cultures including Laos, Cambodia, and Vietnam. As we continue west, we can continue to see dragons in weaving. However, weaving has a special importance to the Southern Caucasus, and due to the silk road, their patterns were taken all over Europe. It is thought the dragon carpets of Azerbaijan and Armenia influenced frescos in Venice and throughout Italy. The mats, mostly carpets and rugs, were usually square, geometric patterns. These carpets are currently being collected throughout the world and returned to their homes to be displayed in museums as an important part of Azerbaijan and Armenian culture.

Vishapakar

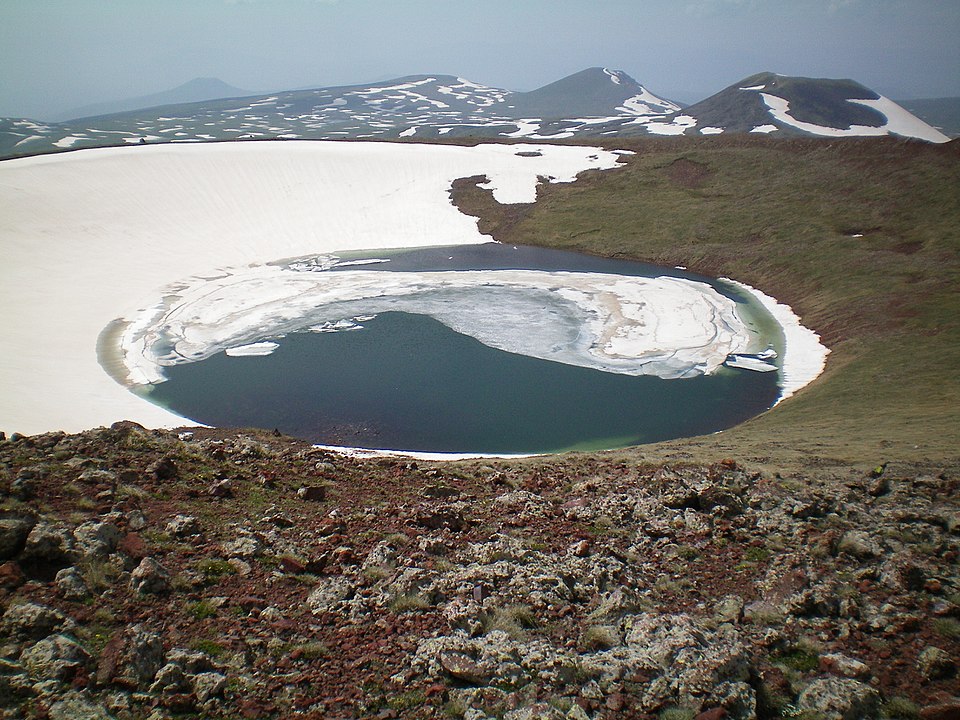

By Hayk, CC BY-SA 2.5, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=1906203

These are large serpent stones, mostly in Armenia. They are tall, skinny stones up to five meters tall, carved with the shape of fish, bovines, or a mix of the two. They are thought to be more than 7,000 years old. Not a lot is known about them, but there are many theories.

Some researchers believe the stones designated water nodules in early irrigation systems. Others believe the stones were used for a ritual purpose, as they were all at high-altitude locations near sources of water. Perhaps this is connected to dragons guarding the sources of water. Others believe the stones were part of fertility cult.

Mythology

In Azerbaijan, people saw the dragon as a creature that blocks the water from reaching the people, and as a cause of droughts, similar to Persian and Indian myths. Since water was thought to be pure and cleansing, the dragons were considered impure and evil. Most Azerbaijan myths involved sacrificing girls to the dragon in hopes that it would stir its tail while eating, which would release the water to the people and the land. This gave rise to heroic figures such as Vahagen, who would kill the dragon and rid the people of famine and drought.

Similarly, dragons in Georgia are associated with water. The Georgian word for dragon, gveleshapi, is actually a composite of whale and serpent, and gveleshapi are believed to have come from the seas but live in the high mountains (and perhaps to have created the seas and earth). Remember the concept of the dragon embodying the underworld, physical world, and heaven from central Asian mythology? Well, the Georgian dragon also connects all three, living close to the sky, on the earth, near clefts that reach the underworld. It’s also worth noting that in ancient Georgian mythology, dragons were considered benevolent and wise. They even showed Georgians where water was, by crawling over it. Over time and with the conversion to Christianity, they became known as evil and the stories of withholding water began to be more common.

Dragon Slayers

The further west we go, the more the stories revolve around the dragon slayers rather than the dragons. These are some of the most popular ones of the region.

By Chaojoker – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=26731941

By Levan Verdzeuli ლევან ვერძეული – Saint George in Tbilisi, CC BY-SA 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=19006387

Vahagn, the Armenian fire god. ( CC BY 3.0 )

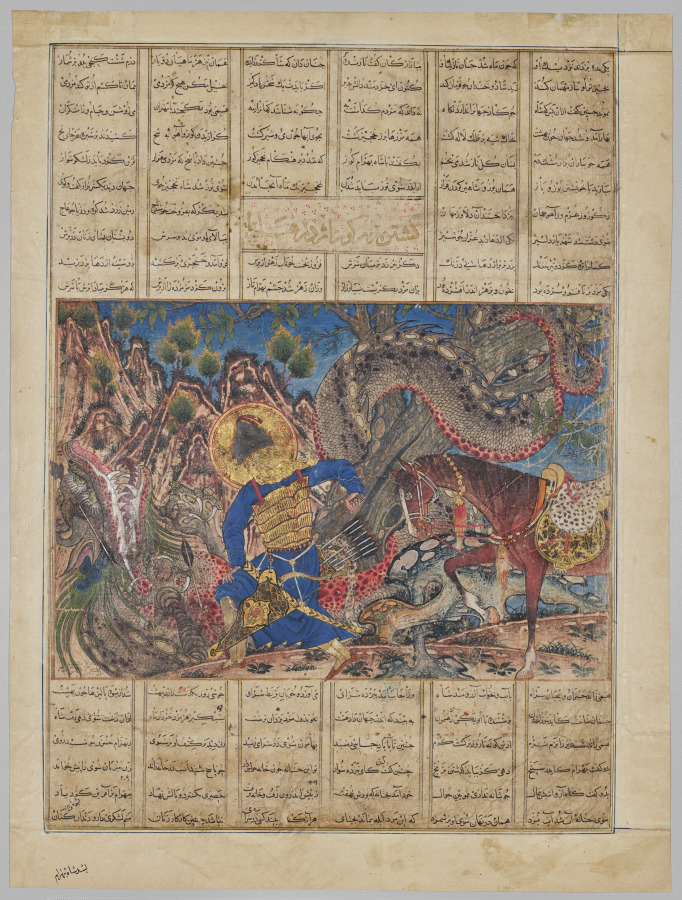

Bahram Gur Slays a Dragon

Vahagen

Vahagen is a deity that was worshipped in Armenia prior to Christianity. Vahagen (or Vahagn) was a fire god, his name derived from a combination of two Sanskrit words –vah (to bring) and agni (fire). In other words, he was known as the bringer of fire, which he used to combat with dragons. After the spread of Christianity, he was demoted from deity to king in the stories.

Bahram Gur

Bahram Gur is a Persian/Iranian hero also celebrated in Azerbaijan literature, most famously in the epic Haft Paykar (The Seven Beauties), by Azeri poet, Nizami-ye Ganjavi (1141-1209). In Haft Paykar, Bahram Gur marries seven women from different nations and learns to rule through their teachings. During the stories he slays various dragons, and these scenes have been made into impressive statues in Azerbaijan. Him slaying a dragon was not only an important representation of good triumphing over evil, but also as the divine right to rule being embodied by kings. Because of this, kings needed to reenact the stories of the gods, such as slaying dragons.

Saint George

We can’t really mention Georgia without Saint George. We’ll get deeper into the many contradictory stories of Saint George in another blog, but one interesting thing is the first manuscript to mention the dragon in Saint George’s story was created in Georgia. (Remember, this was around 500 years after his death).

Besides Saint George, I don’t have specific Georgian slayers. However, there is one interesting aspect to Georgian dragon slayers. The dragon is thought to have omniscience and wisdom, the dragon is related to sorcery and initiation. This means the hero must be swallowed by the dragon, live in its belly to receive the dragon’s power, and then slay the dragon from the inside out. The hero then retains that dragon’s power and can slay other dragons.

In some Georgian traditions, young men had to go through the initiation stages. They were taken away from the village and were physically and spiritually trained. The temporary shelter where the boys were trained had a form of a dragon, which was a visible expression of being in the belly of the dragon.

Bulls and Cows

In both Armenian and Georgian mythology, there are stories of bulls or cows killing dragons. Often, the bull is the symbol of the fire or thunder god. It is thought that the cult of the bull won out in popularity over the cult of the dragon due to the spread of agriculture. Bulls being a domestic animal, they were considered a symbol of human strength to overcome the wilderness.

Aždahak

Aždahak is the Armenian name of the Avestan demon Aži Dahāka, who we talked about in our Persian section. He is depicted as a tyrannical foreign ruler with a demonic aspect: serpents sprout from his shoulders. Aždahak is seen as the embodiment of foreign tyranny. He is also seen as a symbol of wickedness and heresy.

This snake/human form was used to describe many heretics. For example, in an anonymous southern Armenian chronicle dated to the 11th-12th centuries, Moḥammad is described as possessed by demons and breaking free from confinement; the Arab prophet is shown as a heresiarch in terms reminiscent of Aždahak. Similarly, the fourth-century A.D. King Pap, who persecuted the Church and practiced sodomy, is described by the historian Pawstos Biwzand as having serpents springing from his breasts.

In modern Armenia, the stone slabs with snakes and other figures carved on them are called višap “dragon” by the Armenians, but aždahā by the Kurds. In the middle of Armenia, there is a volcanic mountain called Mount Azhdahak, which has several myths about dragons. According to some sources, Azhdahak was the word for half-man, half-dragon, while Vishap was the Armenian name for a full dragon.

Vishaps

Vishaps lived in high mountains or Armenia, in big lakes and in clouds of the sky. Their roar can blast away everything for miles. During thunderstorms, old vishaps from high mountains or lakes fly up to the sky and vishaps in the sky go down on the earth. According to one legend, a thousand year old vishap could absorb the whole world.

And that, my Mythsters, is just an introduction to serpents of the Southern Caucasus! As a reminder, the Mythsterhood is taking next week off, so don’t wait around for a podcast episode or blog post. But you can feel free to poke around the website for old episodes you may have missed, join us in Discord, or join our Patreon for exclusive features. We look forward to venturing into African serpent mythology on January 11th. See you then!

Sources:

Ah! Apparently I forgot to add my sources when I posted this! Luckily, a reader has pointed it out and I am here to fix that. If you want more sources and don’t see them on a blog post, poke us. We may have forgotten.

- Investigation of Meaning of Dragon Motif Designed on Rugs in Aran and Armenia

- Azdaha Dragon, Various Kinds

- Baku Travel Guide: Bahram Gur Statue

- Bahram Gur Slays a Dragon

- Bahram Gur Killing the Dragon

- Lets Talk About the Dragon Stones

- Vahagn: Armenian Dragon Slayer, God, and Bringer of Fire

- Azhdahak: Legends

- Image of Dragon in Georgian Mythology (PDF)

Be First to Comment