Hello Mythsters! In last week’s podcast, I promised you I would expand on Persian dragons in this week’s blog. True to my word, here is what I’ve found about dragons of Persia. There is a lot of ground to cover, so we are going to dive right in.

Azi or Azdaha

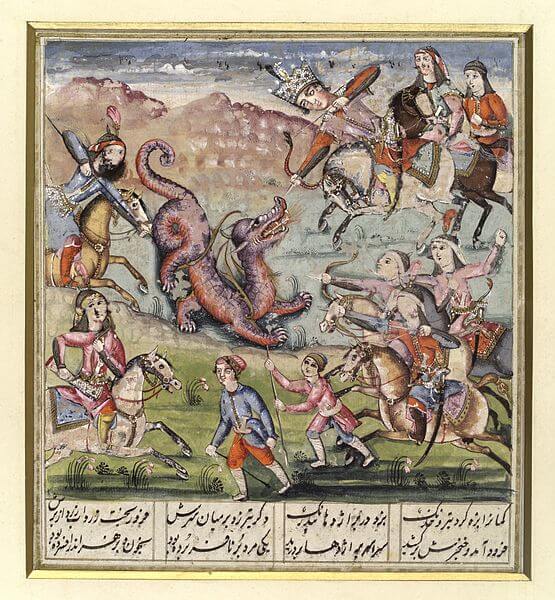

In Zoroastrian tradition, dragons were simply known as azi, or serpents. They had important roles in religious texts. They were mostly demonic, evil creatures who swallowed horses and men and emitted poison. The Persian dragon looked a lot like the Chinese dragon, with a snake-like body. Except its body was surrounded by wisps of flame.

Dragons were almost always depicted as evil in Persian mythology, but there were a few times when they were depicted neutrally, usually at the blending of Persian and Indian culture. This includes some stories of dragons participating in councils with other animals, as part of the greater natural world. In this way, dragons were meant to inspire natural wonder rather than fantastical imaginings.

The other term for a dragon was azdaha, which is the term that seems to have gotten passed throughout central Asia. The azdaha included all types of snake-like, gigantic monsters living in the air, earth, or sea, and they were often depicted on war banners to frighten the enemy. They were sometimes connected to rain and eclipses, much like other Asian dragons.

As opposed to Indian myths, where dragons are slain by gods, in Persian myths, dragons are slain by superhumans. Also worth noting, the dragons tend to behave in very human ways at times, and are perhaps more human-like than even the nagas.

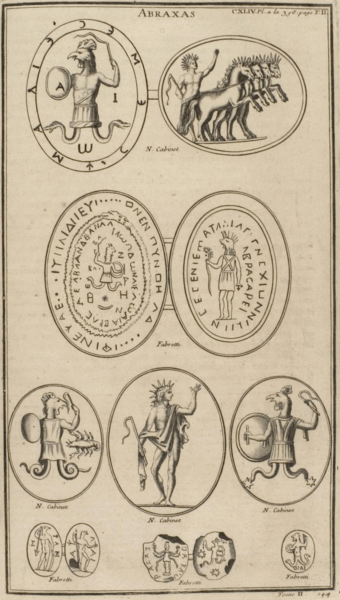

Abracax

Let’s start with an easy one. Everyone knows a bit about Abracax. He was a major part of Greek, Gnostic, Egyptian, Kabbalistic and Jungian philosophies. Okay, maybe that’s not simple, because he represented something slightly different in each school of thought. However, some people believe that Abracax originated in Persian mythology as the sun god, set against Mithra. If Mithra was the protector of truth and justice, Abracax was a creature that could create both truth and lie in a single statement.

Supposedly, Abracax was the creator of the 365 virtues, each one appearing in a man on a different day of the year.

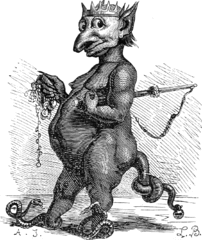

Whatever the mythology behind him, Abracax looked cool. He had the torso of a man, the tail of a dragon the head of a cock, and two legs that were serpents. Not overly dragonish, if you ask me. Which isn’t surprising as he’s often classified as a god, demon, and angel. But the further back you go, the more his lower half becomes serpent-like, turning him into what I might consider a relation of a naga.

Azi Sruuara

Azi Sruuara was the yellow, horned dragon. It was the size of a mountain, swallowed horses and men, and poisonous, apparently with poison flowing from it. It had teeth as large as a man’s arm, eyes as large as a chariot, and a large horn. It was one of the seven worst sinners and skilled in witchcraft.

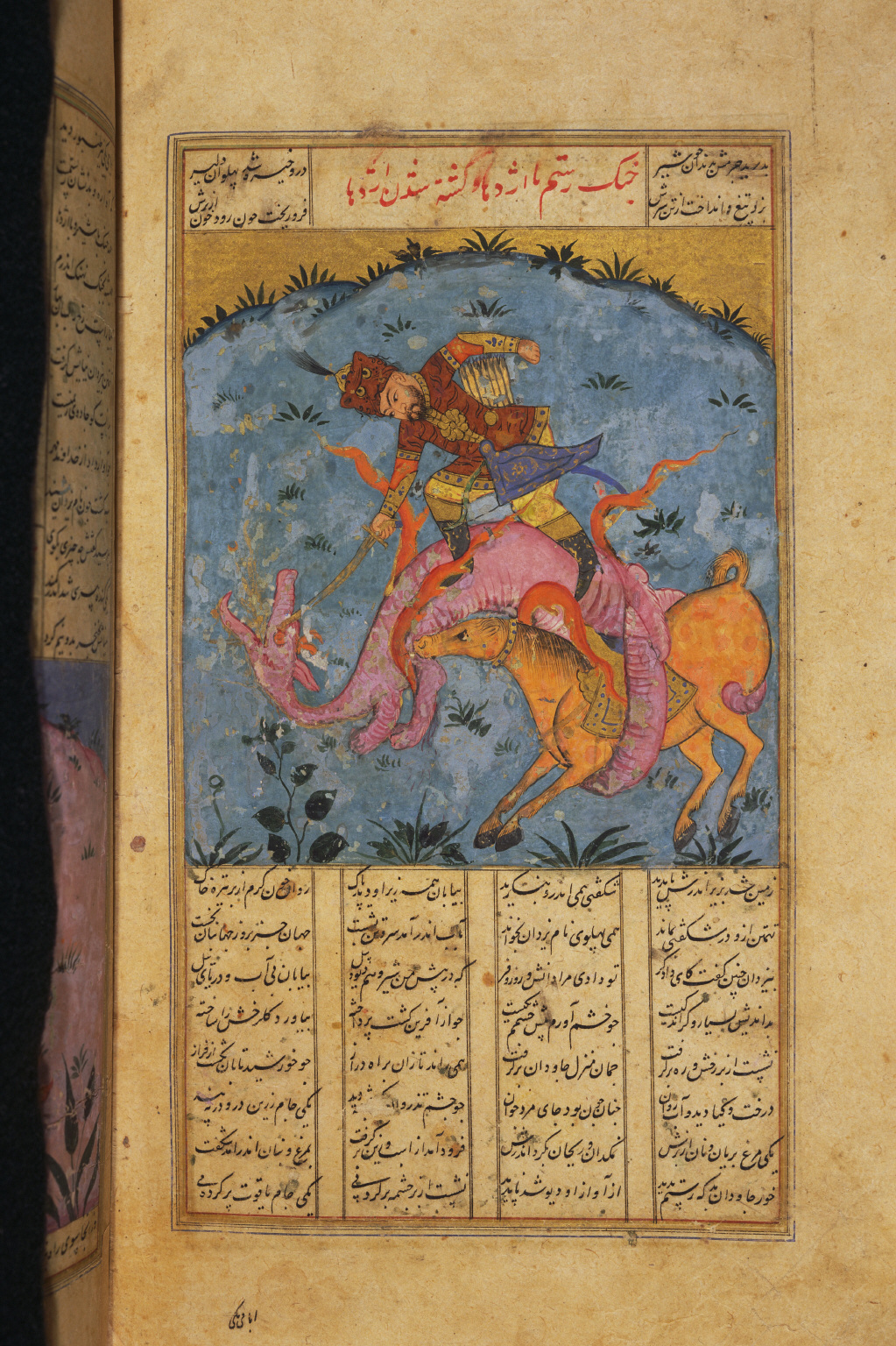

One day, the hero Kirsap stopped on the dragon’s back (thinking it was a hill) to have his midday meal. His fire woke Sruuara, and the dragon stirred and ran. Kirsap ran over its back for half a day until he found its head and killed it.

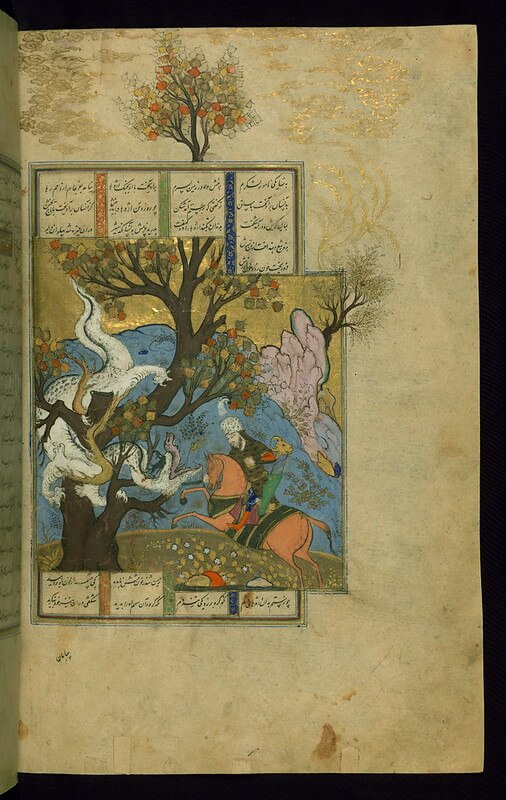

Gandarw

Gandarw is another dragon who was defeated by Kirsap. He’s unique in that he is a water dragon that was large enough to devour 12 provinces at once and so tall that the sea only reached to his knees and his head reached the sun.

Kirsap fought Gandarw in the sea for nine days and nights, and then caught hold of the dragon’s foot and pulled his skin up from his feet to his head, binding him with it. Kirsap then ate fifteen horses and took a rest, during which time Gandarw broke free and pulled Kirsap’s loved ones into the sea. Kirsap awoke and slew Gandarw.

Ahriman aka Drauga aka Angra Manyu

I just wanted to make a note that some people put Ahriman, the prime evil force in Persian mythology, as a dragon or giant serpent. However, I couldn’t find supporting evidence beyond a statue of Ahriman with a serpent wrapped around him, so I am going to skip him for this blog.

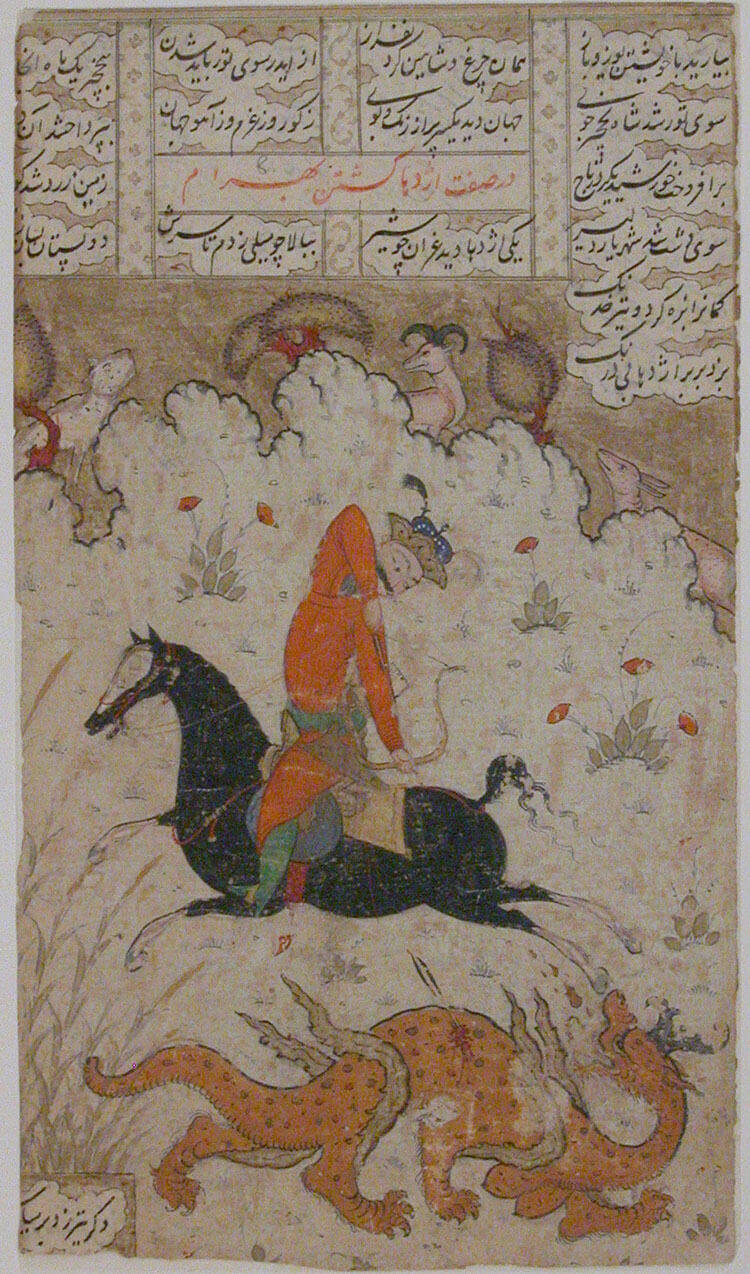

Dahag aka Azi Dahaka aka Zahak

Okay, first I have to ask why every dragon in Persian mythology has to have multiple names? It definitely makes research daunting. And on that note I have to apologize if I get anything wrong in this blog. Please feel free to use my interpretations as a jumping off point to start your own research.

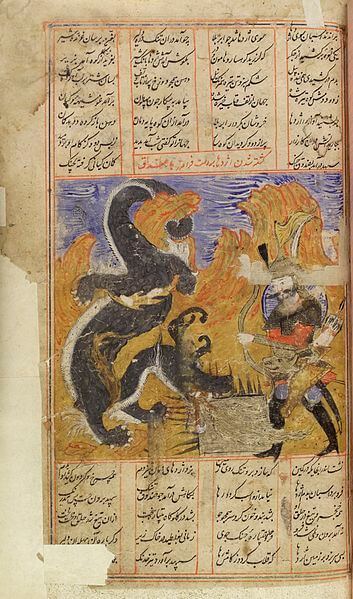

That being said, we’re on to Azi Dahaka aka Dahag. Now, this was either a man-like serpent or a serpent-like man. Either way, I would call him more dragon than man since he is described as having three mouths, three heads, and six eyes. To go with that lovely appearance, he also has a thousand viles and great strength. Oh, and the five defects of greed, sloth, indolence, defilement, and illicit intercourse were his as well. With these traits, he embodied and originated bad religion, everything opposite of good religion.

Apparently, at one point in his early life, he and his brother, Spitiiura, sawed Yima (who was the first of humanity) in half. So, not a great dragon-man. He also captured Yima’s sisters (or daughters, depending on the version) and held them captive while praying to the gods to grant him the power to destroy the entire earth. (spoiler, they didn’t).

At one point, Dahag became ruler of Iran. This was apparently a good thing, because if he didn’t receive the rule, it would have gone to the even more evil Hesm, who had no body and would therefore stay in power forever. Dahag ruled for a thousand years, mixing men and demons and working evil sorcery.

How he got his power was a particularly interesting story, and it may explain the is he a snake or a man issue… but I don’t have space to go into here, so I suggest checking it out at ancient.eu.

Eventually, Frēdōn defeated Dahag when he was just nine years old. Frēdōn first struck Dahāg with his club upon the shoulder, the heart, and the skull, without killing him, and then hewed him with a sword three times, which caused the body of Dahāg to turn into various noxious creatures. Seeing this, Ohrmazd told Frēdōn not to cut Dahāg so that the world should not become flooded with reptiles.

Since he can’t kill him, Frēdōn binds Dahag to a mountain, but he will supposedly be unchained to wreck havoc at the end of time, similar to other religions where evil is imprisoned and released at the end of time.

Gocher and Musparig

Gocher and Musparig are depicted in astrology. Gocher was considered a snake-like creature with his head in Gemini and his tail in Centaurus, and every ten years its head and tail change place.

Musparig had a tail and wings, and and was thought to be the demon who causes lunar eclipses.

Together, Gocher and Musparig were the enemies of the sun, moon, and stars. They were eventually bound to the sun so they could not run free and cause harm. Supposedly, at the end of time, Gocher will fall to the earth with its halo of fire and will melt the metal in the hills, creating a river of molten metal necessary to purify humanity.

And that, my dear Mythsters, is the wonderful note I am going to leave you on. Purified by molten metal.

Until next time!

Koji A. Dae

Koji is a dreamer, a mother, and a writer in that order. The first short story she clearly remembers writing involved fairies losing their wings, and ever since then mythology has found different ways to creep into her storytelling.

[…] is the Armenian name of the Avestan demon Aži Dahāka, who we talked about in our Persian section. He is depicted as a tyrannical foreign ruler with a demonic aspect: serpents sprout from his […]