It always fascinates me when characters migrate from ancient myth and legend and find a place in popular culture–to see them adapting to the times and connecting with younger generations.

Remember Kiyohime–one of the shapeshifters from episode 3? She was one of the main characters in the story of Anchin and Kiyohime. The story has undergone any number of iterations. You’ll find a fair bit of variation in the details but the main elements in the story remain the same throughout. She fell in love with Anchin, a Buddhist monk, who rejected her. She–not at all amused–transforms into a serpent or dragon, chases him, and ends up killing him.

Finding Kiyohime in History

The earliest references to the story I could find mention of are two collections of setsuwa, an East Asian literary genre that, according to some sources, has only a vague definition. Some refer to them as Buddhist tales or fables, delivering moral lessons in the form of a narrative. Others lump all myths, legends, and folk tales into the mix.

Looking at the story of Kiyohime and Anchin, I find it rather hard to classify that as a Buddhist morality tale. “Stay true to your ideal and your stalker person will turn into a dragon and kill you, no matter how far you run.”

Hmm. Just doesn’t quite rhyme for me.

What does seem consistent, is a third definition, referring to setsuwa as stories originally passed down through an oral storytelling tradition. It would certainly account for the many variations in the story.

But I digress.

11th and 12th Century Beginnings

Kiyohime and Anchin’s story appeared in two collections of these setsuwa, respectively Dainihonkoku hokekyō kenki and Konjaku Monogatarishū in the 11th and 12 century.

In these first recorded versions, there’s no mention of the names Kiyohime or Anchin, but I’m going to refer to them by the names because the characters are clearly the same as in the later stories. In either version, Kiyohime is portrayed as a young widow who falls for Anchin, a handsome monk on a pilgrimage to a Shugendō shrine. Anchin attempts to avoid a second encounter by choosing a different route for the journey back. When Kiyohime learns that he deliberately avoids her, she dies of grief. As you would when your crush ghosts you, right?

Wrong. Here’s where we go beyond your run-of-the-mill death by heartbreak. After her death, a serpent exits her bedroom and hunts Anchin down. He looks for refuge in the Dōjō-ji temple, where the monks hide him under a bell. The serpent–presumed to be Kiyohime–catches his scent, and breathes fire onto the bell and kills him.

Years later, Anchin enters the dream of a priest and asks him to copy a chapter of the Lotus Sutra. This would release both him and Kiyohime from continued suffering in their next incarnations. The request was fulfilled and they were reborn separately.

Developing Nuance in the 14th and 15th Century

A third version appeared in Genkō Shakusho in the fourteenth century. This was the first Japanese Buddhist history, written in Chinese and consisting of thirty scrolls. In this version, we first encounter the name Anchin.

A fourth version later appears in a fifteenth century scroll called Dōjōji engi emaki, which translates as Illustrated Legend of Dōjōji. As in the monastery where Anchin sought refuge and got toasted underneath the temple bell. It’s here that–according to Virginia Waters (Waters, 1997)–the story evolves beyond the early versions which focus mainly on delivering lessons in morality, and develops depth and dynamic storytelling.

Here, Kiyohime–though we still don’t officially know this name–is the daughter-in-law of a prominent person. In the earlier setsuwa versions, Kiyohime is evil and lustful, and Anchin an innocent monk trying to protect his purity. When he tells her he’ll come back to her, his lies are justified because they are employed to escape an evil temptress.

In the illustrated scroll, the narrative gains more nuance. Anchin’s seeming discomfort at Kiyohime’s advances is less apparent, and the tale could be interpreted as such that their relationship, as well as their unfortunate karmic connection, is foreshadowed. What’s interesting is that this scroll consists of three interlinking narratives. You have the independent narrator, whose story mostly still conforms to the original setsuwa narrative of a seductress not in control of her lust, and a pure devout monk merely trying to escape this evil. However, the illustrations, and the dialogue lines, if you can call them that, the voices of the characters themselves, add nuance to this portrayal.

This version of the story took on a life of its own, with more iterations in different media, but it will take us until the eighteenth century to actually come upon the name Kiyohime, in the form of a ballad drama or joruri. It was called Dojo-ji genzai uroko or The Scales of Dojoji, A Modern Version.

Later versions again changed the names of Kiyohime and Anchin, but these names seem to be the most prevalent as far as I could find. Some of the stories also claim that Kiyohime was the daughter of an innkeeper, or a servant in a tea house.

In some iterations, Kiyohime’s family provided lodging for travelling priests on their pilgrimages. In some, Anchin even fell in love with her, before overcoming his passions and refraining from further meetings.

Ouch.

However, the versions in which Anchin resists her advances from the start persist as well. In these, he actively avoids her house on his journey back.

In later popular versions, she gives pursuit rather than dying of a broken heart.

In one version, Anchin convinces a boatman to help him cross the Hidaka river, but to not let Kiyohime on board. She–like the badass woman that she is–refuses to let a little water stop her. She jumps into the river and swims after him. Her rage–I doubt it’s her efficient breaststroke–transforms her into a large serpent or dragon as she swims.

Anchin flees to the Dōjō-ji temple and asks the monks for help. They agree and hide him under the temple bell. However, they didn’t take Kiyohime’s new form and her much improved sense of smell into account. She catches his scent, and coils her body around the bell, banging it with her tail.

That must have given poor Anchin a major headache but Kiyohime takes her revenge one step further and breathes fire onto the bell until it melts and kills Anchin.

Another version adds that Anchin’s pilgrimage was an annually recurring event. He and Kiyohime first met when she was a young girl, full of mischief and infatuated with the handsome monk. To get her off his back, he jokingly tells her he’ll come back when she’s of age, and marry her.

When she’s old enough, she reminds him of his promise and he realises that she took his joke seriously. Oops. So he detours on his return trip to avoid her. That’s when she transforms into a serpent and hunts him down. In this context, I can’t say I blame her.

Anchin and Kiyohime provide a riveting tale that continues to inspire new iterations time and again. Among others, it forms the basis of a collection of plays termed Dōjōji mono or Dōjō-ji Temple plays, depicting the event that destroyed the temple bell. The plays were written for different theatre traditions like Noh (Dōjōji) and Kabuki (Musume Dōjōji).

Contemporary Takes

In more contemporary works, we encounter Kiyohime in a few video games.

Fate/Grand Order

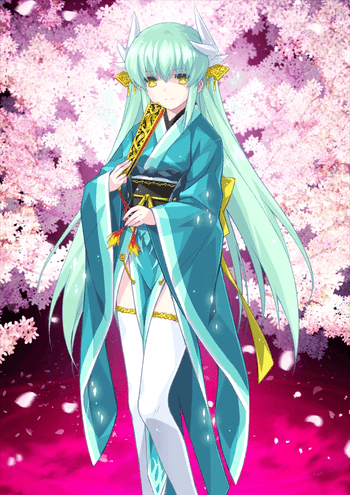

The most prevalent in my searches was, without a doubt, the mobile game Fate/Grand Order. According to Wikipedia, she has a dual role, as both a Berserker and Lancer class servant.

The game even refers to the bell she melts to get to Anchin, in a spell or attack aptly named Scorching Embrace.

Megami Tensei

Further, she incarnated a second time in a video game series called Megami Tensei, where she’s portrayed as a demon.

For Honor

In For Honor her appearance is more obscure. She’s not literally present, but forms the inspiration for a sword gear set named “Kiyohime’s Embrace” with serpent scales on the blades’ hilts and marks on the blades that look like they’re affected by immense heat, or partly melted.

Onmyoji

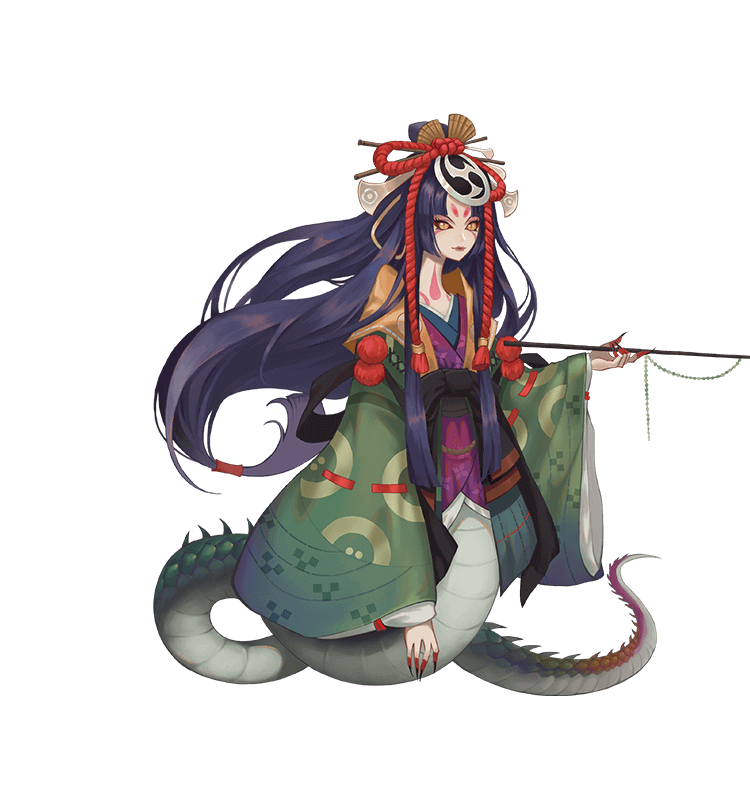

In another mobile game, Onmyoji, Kiyohime reincarnates yet again as a fire-spitting snake-like spirit as well as an occasional villain.

Hellboy Animated: The Menagerie

In 2007, Dark Horse Comics released Hellboy Animated: The Menagerie #1, in which Kiyohime makes a guest appearance. I couldn’t find much about her role in the story.

However we do see her pictured along with the signature temple bell yet again.

My-HiME

Lastly, as far as I could find, she features in the anime series My-HiME. Here, she is a strange hybrid of spiritual and mechanical being and one of the 12 HiMEs.

Now, I may have missed other iterations, but whenever the name Kiyohime appears in a keyword combination, the search is overwhelmed with hits for Fate/Grand Order. It was quite a challenge to sift other results from in between.

If you did find other iterations, we’d love to discuss those with you on Twitter or in the comment section.

Jasmine Arch

Jaz, also known as the Wolf Mother, is a writer, poet, narrator, and vessel of chaos. She is eternally grateful for her mother’s refusal to curtail her children in their choices–whether that was literature, spirituality, studies, or appearance–and grew up devouring her older brother’s collection of fantasy novels. In hindsight, telling stories of her own seems inevitable, but it took her a while to accept this and find the courage to begin.

Sources:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kiyohime

https://www.encyclopedia.com/religion/dictionaries-thesauruses-pictures-and-press-releases/setsuwa

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Setsuwa

https://www.jstor.org/stable/30233169?seq=1#metadata_info_tab_contents

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Genk%C5%8D_Shakusho

Waters, V.S. (1997). Sex, Lies, and the Illustrated Scroll: The Dojoji Engi Emaki. Monumenta Nipponica, 52(1), p.59.

https://www.yokaistreet.com/kiyohime/

https://comicvine.gamespot.com/kiyohime/4005-27798/

Be First to Comment