Hello Mythsters! Didn’t get enough info about Japanese Dragon lore in last week’s podcast? Don’t worry. We’ve got you covered with a supplemental blog post. Strap in, because there’s some good stuff here.

Centering the Hero

Dragon mythology serves different purposes in each culture. As we saw in Australia and many Pacific Islands, dragons serve as a creation myth. As we go further west, dragons will take on cautionary roles in morality tales. In Japan, dragon mythology tends to center the hero. What’s that mean? Well, that the dragon is not the main character but either a force the hero must overcome or serve during the tale. This puts the focus on the effort of the human rather than the power of the god.

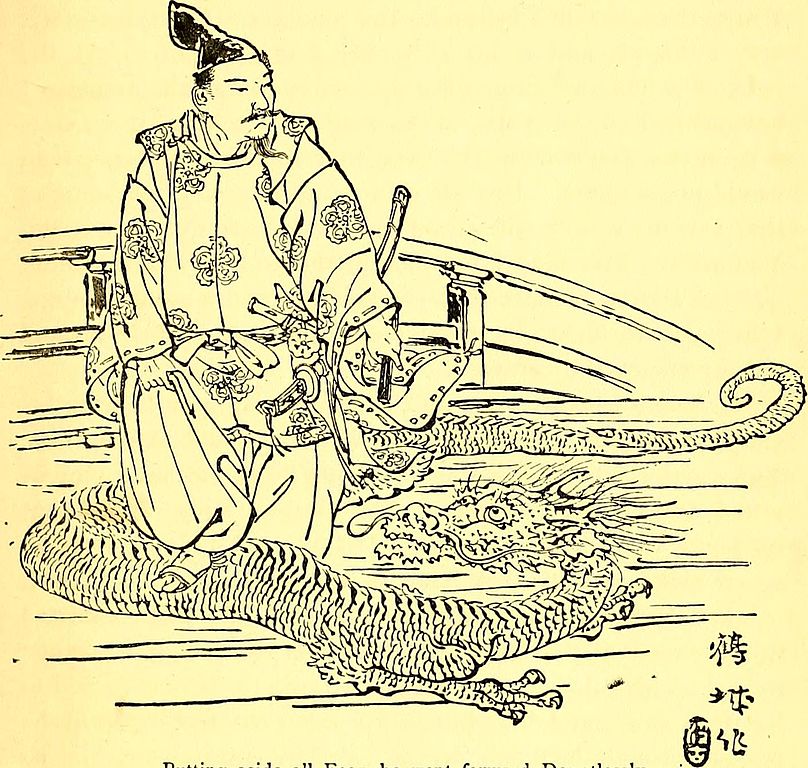

My Lord Bag of Rice

This tale centers the hero Tawara Toda, who is a true warrior and cannot bear to be idle, so goes off seeking adventure. In his journey he meets the dragon king of Lake Biwa. The dragon kind takes the form of a dragon, trying to find a brave man to kill a centipede who has been abducting his family. Most men flee from the dragon, but Tawara Toda does not falter. When the dragon king turns back to a man, he explains about the centipede and Tawara Toda slays the beast. The dragon king rewards him with a never-ending bag of rice, hence the name.

The really interesting thing about this tale is that the dragon, a deity of sorts, with mystical powers, was dependent on the human hero to save him and his family. If you take into account how tied up Japanese deities are with nature (I’ll get into that later), this shows how men are needed to protect nature and keep balance in the world. It puts a lot of powerful pressure on mankind. But in a good way, because the hero always wins.

Dragon As Sea Monster

Some Japanese stories refer to the kuma-wani, which is a large shark or crocodile creature. From what I read, they seem a lot like the taniwha in Maori legends. These are generally lower-gods or not gods at all but giant sea beasts.

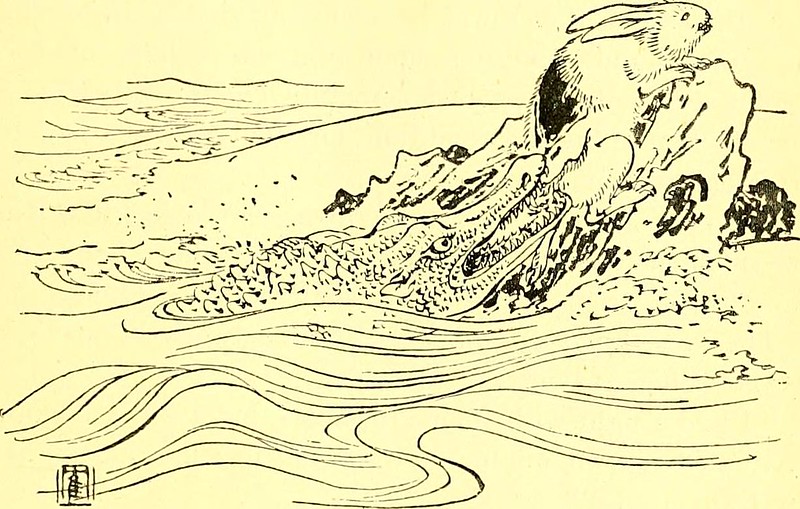

The White Hare of Inaba

In this story, a hare tricks a crocodile to gather its friends and make a bridge across the sea so the hare can cross. The hare mocks the crocodiles for their stupidity and they tear out his fur. In this story the crocodiles have no special powers beyond speech, so it feels more like a morality fable than a full-on mystical myth.

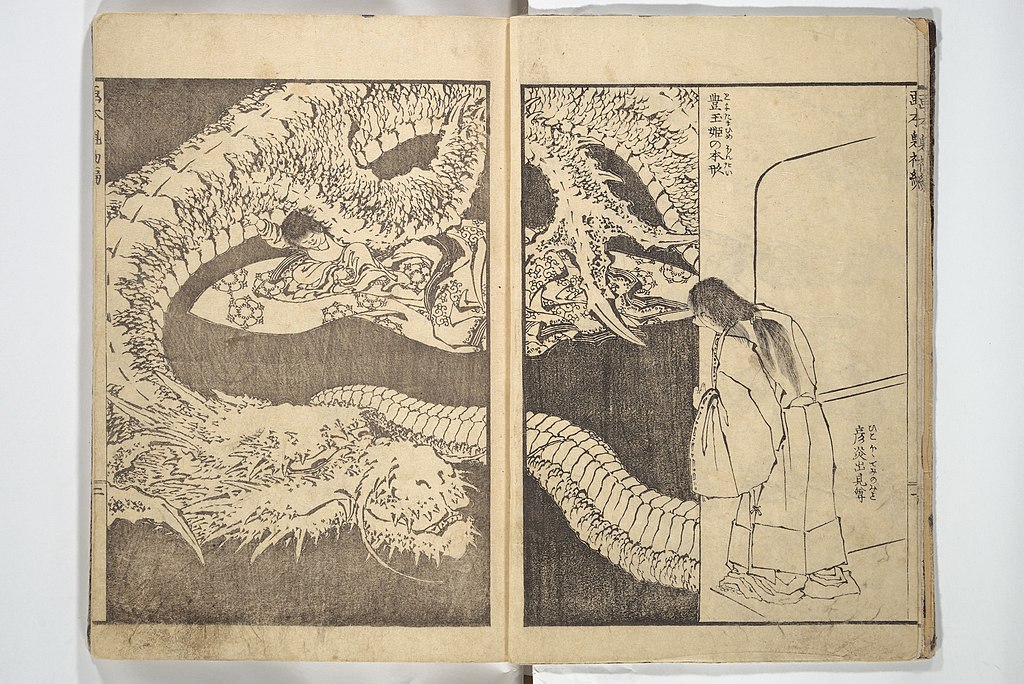

Toyatama-hime

Toyatama-hime was the sea-king’s daughter who married a hunter prince named Hoori. I love this story because it was she who was struck with his beauty and asked him to marry her — kinda puts a spin on traditional gender roles. They lived awhile under the sea, but ultimately return to land where Toyatama gets pregnant. To give birth, she must turn into her natural form, which is a wani.

Hoori promises not to look, but his curiosity gets the better of him and he sees a giant crocodile cradling his baby. Ashamed at what Hoori had seen, Toyatama abandons him and her son, returning to the sea.

Dragons as Kami

The Shinto religion has a belief called Ryūjin shinkō (“dragon god faith”). In this belief, dragons are considered to be water kami. A kami is a sacred spirit, sort of like a god. Dragon kami are associated with agriculture, rain, and fishermen. Many Shinto shrines for hand washing feature dragons because they are thought to dislike filth and prevent disease.

Fukuryu

The Fukuryu is known as the good luck dragon in Japan. They are depicted as ascending into the skies, towards success and have a certain amount of vitality to them associated with health and strength. This sounded very similar to Chinese dragons to me, and I went looking for more information but came up short. What I did find was that for being a luck dragon, the name Fukuryu was associated with some rather dark events.

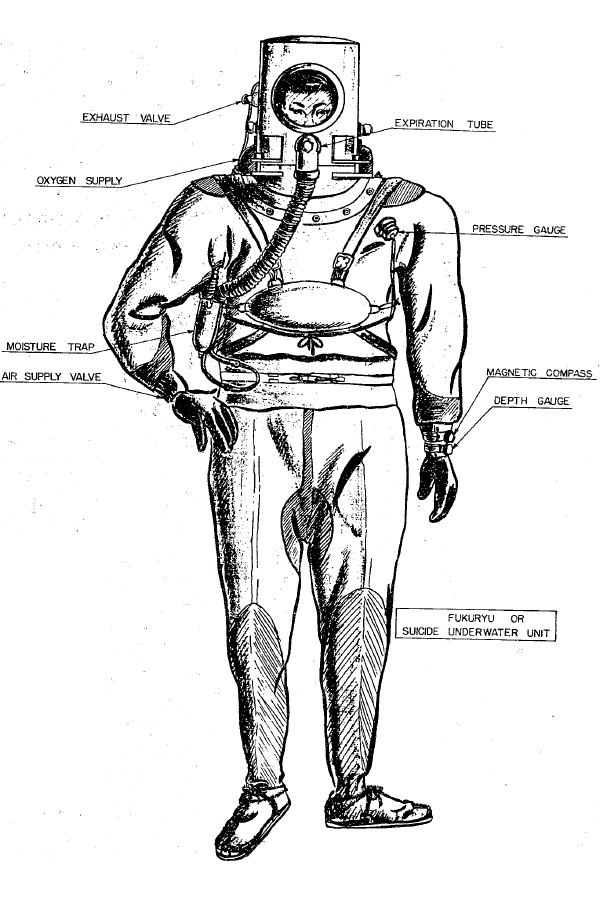

Japanese Special Attack Units

During World War II, a special attack unit called Fukuryu was conceptualized in Japan. These units were meant to live underwater in a small box for ten days at a time, waiting for enemy ships to pass over. They would then attach bombs to the ships, taking out the ship and dying in the explosion. They were also known as suicide divers and kamikaze frogmen.

The Daigo Fukuryū Maru

Lucky Dragon 5 was a tuna fishing boat that was contaminated by the fallout from the US Castle Bravo thermonuclear weapon test on March 1, 1954. The ship was supposedly out of range of the test, but the test ended up being twice as powerful as expected and the wind blew the nuclear fallout over the ship.

Fourteen days later, the ship returned to Japan. The crew was suffered from radiation sickness and the boat and fish were contaminated. Over the years, Lucky Dragon 5 became a symbol of the anti-nuclear movement in Japan and is currently on display at the Tokyo Metropolitan.

As a side note, Godzilla was partially inspired by this event. The ship is featured on the 2001 poster for Godzilla, Mothra, King Ghidorah: Giant Monsters All-Out Attack.

This, and our podcast, just licks the tip of Japanese dragons. I definitely hope to come back to them sometime in the future. But until then: Heading West!

Koji A. Dae

Koji is a dreamer, a mother, and a writer in that order. The first short story she clearly remembers writing involved fairies losing their wings, and ever since then mythology has found different ways to creep into her storytelling.

Featured Image:

“Ryu sho ten” or “Ryu shoten” (Dragon rising to the heavens), also known as “Gekko Zuihitsu” (Gekko’s Sketch), a Ukiyo-e print from Ogata Gekko‘s Views of Mt. Fuji. A dragon rises out of smoke near Mt. Fuji, ascending towards the sky.

The text on the left hand side is in an archaic form of Japanese writing that includes characters not in common use any more. translation follows:明治卅年十一月一日印刷同月五日発行印刷兼発行日本橋区吉川町二番地松木平吉Printed on Nov 1st, 30 of Meiji [1897], published on the same month 5th. Printed and published by Heikichi Matsuki, who lives 2 Yoshikawa, Nihonbashi ward.

Be First to Comment