So, as mentioned in episode 13 of the podcast last week, of course there are more than two dragons to be found within Egyptian mythology and folklore.

Let’s follow the trail of cookie crumbs left in the episode, which led us from one of Ra’s protectors, Wadjet, to one of his nemeses, Apep. From there, it leads us to another serpent.

Mehen

His name means coiled one, and he’s often depicted coiled around the Boat of the Sun, in which Ra traveled every night, and in which he then had to face–and preferably defeat–Apep.

The earliest references to Mehen, go back to the Coffin Texts–a collection of funerary spells written on coffins dating from the First Intermediate Period, after the end of the Old Kingdom. Unlike the pyramid texts they were derived from, these were accessible to common people as well as Pharaohs, meaning that, if you had enough cash to afford a coffin, you got to have an afterlife too.

One of these texts, numbered 1130 to be precise, is a speech by Ra himself. The line that stood out to me immediately is this one:

Hail in peace! I repeat to you the good deeds which my own heart did for me from within the serpent-coil, in order to silence strife …

A reference to Mehen perhaps? Beyond the use of this serpent in funerary rites, we also find her in another, most unlikely place. You see, Mythsters, Mehen is also the name of a board game played in ancient Egypt. Now, apparently, there is not that much to be found about the nature of the game, or its relationship to Mehen. The board depicts a coiled snake, but it’s a bit of a chicken-or-egg problem, as it’s not quite clear whether the game was derived from the creature or the creature from the game.

A game you say?

We do know it’s a game rather than a religious carving, as this is shown in paintings inside tombs. The way the ancient Egyptians played has not been discovered, but rules have been created in modern times, based on assessments and guesswork of how it might have been played.

With some digging, I managed to find a comprehensive tutorial on YouTube. Now, it does look a bit complicated, I’ll admit, but it also looks like a ton of fun. I mean, a game in which I can actively thwart my opponents rather than just trying to outrun them? I am so here for that.

The video below gives some more detailed explanation on the game so definitely check that out if you’re interested. For the more adventurous mythsters among us, click here for a printable version of a Mehen board. Instead of the sticks you throw to see how you can move, you could just use six-sided dice and see if they come up even or uneven, and pawns can be borrowed off any chess board, of course.

Another ancient Egyptian trendsetter

So, remember how there is a plausible reason to assume Wadjet from the podcast episode lay at the root of the caduceus symbol? Well, she wasn’t the only ancient Egyptian trendsetter. Our friend Mehen may very well lie at the root of the Ouroboros symbol, which depicts a snake eating its own tail. In fact, the earliest known depiction of such a serpent was found on one of the shrines by Tutankhamun’s sarcophagus.

The text in which it featured was called the Book of the Netherworld and it describes Ra’s actions as well as his union with Osiris in the underworld. The Ouroboros can be seen twice, one circling the head and chest of a tall figure, the other the feet. This figure might well be the unified Ra-Osiris, or Osiris reborn as Ra.

In other Egyptian sources, Mehen symbolises the disorder that surrounds the orderly world. Sound familiar at all?

So, let’s move on to our next dragon, shall we?

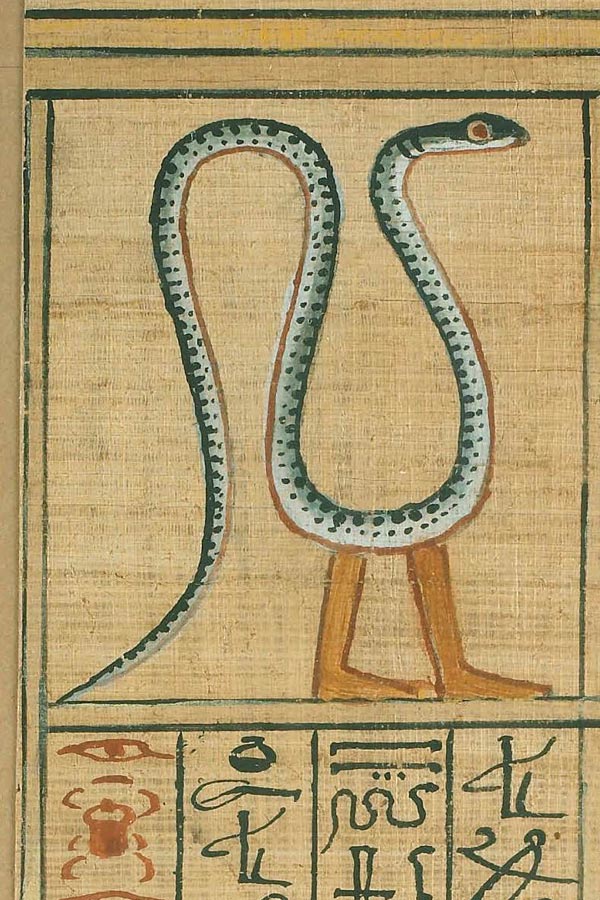

Nehebkau

Our next serpent is called Nehebkau, a primordial serpent. He was often depicted as a snake with arms and legs, occasionally with wings as well. Sometimes, he carries containers of food to offer to the deceased. Sometimes, he has the body of a human but the head and neck of a snake. Less common is the depiction of him as a two-headed snake, with a head at each end of the body.

Although he began his career as an evil–or at the very least mischievous–spirit, later he cleaned up his act and took on the responsibilities of a funerary god with a strong association to the underworld. He was one of the forty-two assessors of Ma’at–deities charged with judging the souls seeking entrance to the afterlife.

By the end of his reign, he was considered a powerful, benevolent, and protective deity. At this time, he’s described as a companion of the sun god, as well as an attendant of the deceased King. His festival was well-known throughout the Middle and New Kingdoms.

In some stories, he is said to be the son of one of three deities, Serket, Renenutet, or Geb. In others, it was believed that he simply emerged from the earth. Apparently, egyptologists have struggled to agree on what exactly his name stands for, and they’ve come up with a number of different translations: That Which Gives Ka, He Who Harnesses the Spirits, the OverTurner of Doubles, Collector of Souls, Provider of Goods and Foods, and Bestower of Dignities. Many of these names do seem to refer to the duties he performs for the deceased.

In one myth, he swallowed seven cobras, rendering him immune to harm by magic, fire or water. I would advise against trying this life hack at home, though. In an earlier rendition, he also displays fire-breathing capabilities (another fire breather, yay).

In his earlier days–back when he was still a rebel–he was accused of devouring human souls in the afterlife. That made him the enemy of the sun god, who–or so they believed–built his sun boats to catch the wind and escape the many coils of Nehebkau’s body. However, in the Coffin Texts, we do find one reference to Atum subduing his chaotic and fierce nature, merely by placing a fingernail against a nerve in Nehebkau’s spine, and this is when he became one of the good guys.

It was only later that he was honoured among other dangerous gods as one of the forty-two judges tasked with the assessment of newly deceased souls in the Law-court of Osiris, also known as the Dead Court. I guess the ancient Egyptians believed in a tough-love policy when it came to sin and penance. He was also responsible for guarding the gates of the underworld, and as such, he was still a fearsome creature.

However, he has more nurturing aspects as well. To those who can stay on his good side, he can be a helpful ally, and after abandoning the dark side, it was said that he provided the deceased King with food and assistance in the afterlife. Once a soul was declared innocent in the Dead Court, it was Nehebkau who absolved the soul of sin and provided food and drink, as well as ka, the life force a spirit needed in order to endure in the afterlife. The living, on the other hand, invoked him to protect or cure them from venomous bites, probably because he’d proven so skilled at swallowing cobras.

So, after this bad boy with a redemption story, let’s turn to our next dragon.

Ammut

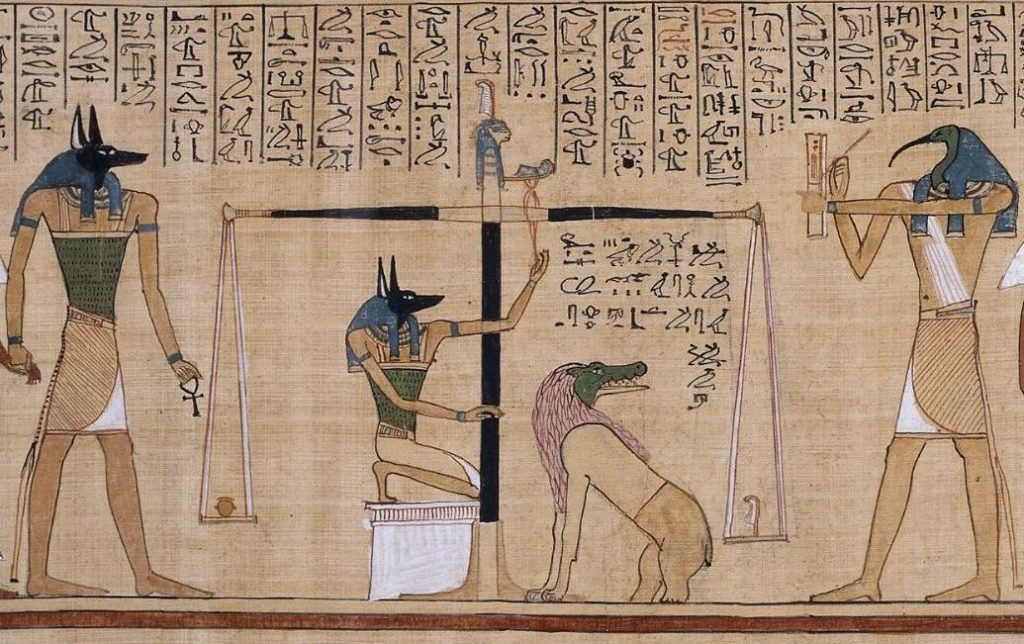

Ammut, also known as Ammit, Ahemait, or Ammemet, bore illustrious (and slightly terrifying) titles such as The Eater of Hearts, The Devourer, and Great of Death. I’ll give you three guesses as to her job description. Yup, she was a colleague of Nehebkau. Ammut also took part in the Dead Court, where the heart of the newly deceased was weighed on the scales of Ma’at. The counterweight? The feather of truth. No pressure guys.

An unworthy sinner became Ammuts dinner, and this would mean a second–and final–death. The soul would then become restless forever.

Ammut has a very interesting appearance as well. It’s been a while since we came across a chimera-type dragon, but here she is. With the head of a crocodile, the body of a leopard, and the hind quarters of a hippopotamus, she must have cut quite the imposing figure. All of there were fierce creatures, and all were known to the Egyptians as not being too averse to snacking on the occasional human.

The above image shows Hunefer’s heart in the middle of being weighed on the scales of Ma’at. On the other side lies the feather of truth. It’s jackal-headed Anubis doing the heavy lifting here. The result is then recorded by Toth, who has the head of an Ibis and acts as divine scribe. If the heart it heavier than the feather, Ammit sits poised and ready to devour it and Hunefer will not pass on to the afterlife. If the heart is lighter, she will have to go hungry a while longer.

Ammit, poor thing, was not worshipped by the people of ancient Egypt. She embodied all they feared most and was a constant reminder of the threat they faced if they didn’t uphold the principles of Ma’at: eternal restlessness.

So, after two gods who might have been scary but really held the good of humankind, and the principles of Ma’at in their thoughts, let’s move on to an irredeemable bad boy.

Denwen

AKA The Fiery one.

Now, Denwen was no serpent to be trifled with. He, like Nehebkau, posessed the ability to breathe fire. But he was believed to be capable of such powerful flames it could create an extinction event for the entire Egyptian pantheon. According to the Piramid Texts, the dead pharaoh put a stop to that.

Egyptians, considering him the embodiment of absolute evil (no redemption for Denwen), wisely kept their distance from this bad boy. Perhaps this is why I couldn’t find anything more about him. I couldn’t even find out how he looked or which of the deceased kings kept him from roasting all of the other gods. It’s probably like with Sauron, and we’re not supposed to use his name or anything, lest we draw his attention. Too late for that though. Oops.

Hi there, Denwen, old buddy.

So was that all?

I came across two more names but didn’t them include in this article: Aker and Ankh-Neteru.

In the case of Aker, I found other sources describing him as a lion rather than a serpent or dragon.

For Ankh-Neteru, I only found the same paragraph repeated in different locations, so that’s not a lot to go on. If you should find something more about him, we’d love to hear about that.

And that, indeed, is all she wrote. For now at least. I have to say the thought of a redemption plot within dragon mythology intrigues me to no end. I do hope we’ll come across more of these in future episodes. Which was your favourite? Do let us know on Twitter, or hop into our Discord Server.

Later Mythsters!

Sources

- https://nl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ammithttp://www.dragonsinn.net/middle_east6e.htm

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mehen

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Coffin_Texts

- http://www.blackdrago.com/fame/mehen.htm

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nehebkau

- http://www.touregypt.net/featurestories/nehebkau.htm

- https://www.artic.edu/artworks/140647/amulet-of-nehebkau

- https://www.jstor.org/stable/3854489?seq=1

- http://www.blackdrago.com/fame/nehebkau.htm

- http://www.blackdrago.com/fame/denwen.htm

- https://theancientworld.fandom.com/wiki/Denwen

- https://cooldragonstories.weebly.com/egyptian-dragons.html

- http://www.touregypt.net/godsofegypt/ammut.htm#:~:text=Ammut%20(Ammit%2C%20Ahemait%2C%20Ammemet,fierce%20creatures%20to%20the%20Egyptians.

Be First to Comment