So, with a slight delay while we catapulted some of life’s lemons back to whence they came, we’ve finally come to the promised blog post about some of the hybrid dragons encountered in Greek mythology. Considering the amount of offspring from Typhon and Echidna alone, you just know we can’t possibly discuss them all.

But there’s only one place to start: with the creature that forever lent its name to the genetic variation that leads to a cell within a single organism expressing different genotypes, which means the DNA encoded within the cell’s core is fundamentally different from that inside another cell. The very definition of the word hybrid.

This anomaly is referred to as Chimerism, and the organism as a…

Chimera

Of course we had to start here. While its outward form may not look like we’d expect from a dragon, it’s got one characteristic we’d certainly associate with a dragon: it breathes fire.

This mythological mash-up hailed from the region of Lycia, in what was known during its heyday as Asia Minor. But today, that region is the provinces of Antalya and Muğla, on the southern coast of Turkey.

But when we say mashup, that’s sometimes a bit hard to visualise, no? With most hybrids, heads seem to go wherever a head belongs, and the same goes for tails and other assorted body parts, even if they did at some point belong to different animals. But the Chimera really is something special.

Picture a lion. Big teeth and claws, voluptuous mane, loud roar… Got that image in your mind? Good, now let’s add a head, but it doesn’t go next to the other head, as you’d imagine. Nope. A goat’s head protrudes from the creature’s back. While it’s excellently placed to spot aerial attacks, I don’t see much other use for it. That goat’s grazing days are over. But we’re not done yet, of course. The Chimera’s tail is a snake, although Hesiod in his Theogony actually uses the word dragon instead of serpent or snake.

Now, while many contemporary texts refer to the Chimera as an it, Hesiod uses feminine pronouns to refer to the beast, and upon comparison to other depictions of lions, one might concur, despite the fact that the Chimera clearly sports a mane. A close mane was typically shown on any image of a lioness, but the ear would always show, whereas a lion, in artworks, didn’t have its ears visible, implying their mane was longer.

This curious beastie was actually one of the many children of Typhon and Echidna–which we mentioned in episode 18 of the podcast–and which means that among its siblings, the Chimera can count Cerberus and the Hydra of Lerna.

According to some sources, Chimera produced offspring of her own, through a mating with her brother Orthrus, a two-headed dog much like Cerberus. Their children would have been the Sphinx and the Nemean Lion, who was later vanquished by Heracles as one of his great works. However, some ascribe a different parentage to these two, citing a mating between Orthrus and Echidna. And really, most sources claim that the two were merely part of the larger brood of Typhon and Echidna, placing them as siblings to the Chimera rather than her offspring.

After a decent run of terrorising the Lycian region, Chimera was slain by Bellerophon with the help of Pegasus. Because of Pegasus, Bellerophon was able to shoot arrows from a safe height, out of range of her flames. For the finishing blow, he fitted the end of a spear with a lump of lead, which melted under the heat of Chimera’s breath, and poured down her throat.

But when I think about complex creatures like this, their abilities and erratic physical form, I can’t help but think about where they came from. Especially in this case where, as with the Drakon Indikos before it, we have a creature not native to Greece, but representations of her in both art and literature are Greek, with a bit of Etruscan art thrown into the mix.

So let’s dive a bit deeper. An article by Marilyn Low Schmitt in the American Journal of Achaeology from 1966 called Bellerophon and the Chimera in Archaic Greek Art suggests that the myth may trace back to more than one origin point, based on variations in the extant visual representations of the myth. Specifically, pre-Corinthian and Corinthian artists had a period of immense fascination with the Chimera-Bellerophon myth, developing more into a focus on the monster as a motif, thereby losing track of the context of the story.

We see development of separate depictions of the Chimera on the one hand, and Bellerophon and Pegasus on the other hand. Now, this tradition falls into a lull some time before 630 BCE. During this lapse, however, we see Chimera depictions appearing on Attic vases. Four strong representations of the Attic version of the motif are identified by Schmitt, with some highly noticeable differences from the Corinthian versions.

Instead of the fire coming from the lion head’s mouth, in two of the Attic depictions, it’s the goat’s head that breathes fire. But one other piece is even more unique, in that it is much closer to the literary concept of the monster than any other artwork before it.

Though fragmented, researchers managed to reconstruct a Chimera in which the goat part of the monster is not just a head, but a complete body, almost to the hindquarters and the whole lion’s body turns into that of a great serpent at the waist, leading to a much more balanced hybrid form than we’ve seen so far in artworks, where before we had essentially a lion with some extra bits.

This piece is in possession of the Athens Archelogical Museum. Just another reason to go and visit Athens, right?

While not all Attic Chimeras are equally distinguished from Corinthian ones, they do all have one thing in common: the lion and goat’s heads face to the rear. The differences lead her to believe there is a different origin, rather than just being a reinterpretation.

By the end of the century, we have records of three distinct Chimera types within Attic and Corinthian vase painting traditions. You had the lion-with-extra-bits version, with both goat and lion’s head facing forward, the rather unique dragon-chimaera with the rear body of a serpent and both goat’s and lion’s head facing the rear, which seems to be rather unprecedented according to Schmitt’s article, and then there was a sort of in-between version.

A lion-with-more-extra-bits: in this depiction, the goat’s head has been replaced by a full goat’s protome (head and upper body). Again, both lion and goat are facing their rear.

Now, while the historical development of the motif alone fascinates me enough for a week’s worth of rabbit-hole diving and side quests, I’m still no closer to sussing out where the actual myth came from.

Pliny the Elder, citing Ctesius and Photius, hypothesised the myth may have originated in an area you can still encounter today, in Turkey, called the Lycian Way, or Yanartaş (flaming rock) in Turkish. The area contains about two dozen permanent gas vents on the hillside above the temple of Hephaestos, near ancient Olympus, in Lycia.

Burning methane coming out of holes in the ground would be quite scary to the ancient traveller, and it’s not unreasonable to assume that might lead them to believe a monster lurked in the area. However, I didn’t find much confirmation beyond Wikipedia so far.

While I may return to it later, I had better move on to our next hybrid for now.

The Gorgons

While depictions again vary, we know them best as three sisters with hair made of living, venomous snakes. To look at them was enough to turn you to stone.

The name that will come to mind, of course, is Medusa, but her sisters, Stheno and Euryale were the immortal ones. Medusa, on the other hand, was mortal.

But of course, there’s more here than meets the eye. Homer, as the author of the oldest known work of European literature, merely mentions one Gorgon, whose head is displayed as a trophy.

…and therein is the head of the dread monster, the Gorgon, dread and awful…

Homer, Iliad

In fact, it’s not thanks to our old friend Hesiod, that we get to that number of three. He depicts them as sea daemons: Stheno, the mighty, Euryale, the far-springer, and Medusa, the queen. Something makes me wonder why the mortal sister is the one to be named the queen, and what that says about how Hesiod viewed the relationship between gods and mortals…

But I really do need to try to minimise the side quests here. Our Gorgon sisters are the daughters of two lesser sea deities: Keto and Phorcys, and their home is on the farthest side of the western ocean, although later sources place them nearer to, or in Libya.

According to Ovid, a later Roman poet working in 8 AD, Medusa was the only one with a hissing venomous hairdo. Book IV of his Metamorphoses, a narrative poem consisting of an impressive 11,995 lines, 15 books and over 250 myths, tells the story in a rather more nuanced way, but only if we look at what floats beneath, since Ovid tells the story through the eyes of Perseus.

Medusa was reputed to be the most beautiful of the Gorgons, known for her lovely hair. It was Athena who cursed her, turning her hair into living snakes as a punishment for violating her temple by Poseidon. Of course, being a Roman, Ovid calls them Minerva and Neptunus but we know better, right? As a result of the curse, anyone who looked at her would turn to stone. Perseus killed her and cut off her head. He circumvented the curse by looking at the reflection of her in his shield, rather than directly at her face or figure.

So, let’s just say I’m not really a fan of Perseus. Not only did he kill Medusa only to turn her into a trophy and a weapon by using her head to turn his enemies into stone, but he conned the Graiae, the Gorgon’s sisters, into giving him the items he’d need to defeat her.

With their help, which they didn’t exactly provide willingly, he acquired winged sandals that allowed him to fly, the cap of Hades which made him invisible, and a curved sword with which he would decapitate their own sister.

But at no point ever do we hear or see what she–or any of the other women in the story for that matter–thinks or feels. It’s Perseus who gets to tell his story in the Metamorphoses. Medusa is a prize to be claimed, a symbol of his heroism.

We have to look at the story floating beneath the surface, if we want to see Medusa the way she deserves it. We don’t know what she thought, felt, or wanted. It’s not until Bernini, who sculpts her at the moment of transformation and captures the despair and agony she must have gone through, that we see her depicted as anything but a monster.

The moment of transformation is suggested in the shape of the snakes, as not all of them are equally well-defined. It’s as if they’re caught in that moment of finding their shape.

This image, in which you see her realising her fate, and living the pain of what’s been done to her, makes her feel so real and human that it becomes rather heartbreaking.

Yes, I most certainly am a fan of Bernini.

For example, while some of Ovid’s later translators and interpreters speak of an affair between her and the sea god, it may be reasonable to assume she had no choice in the matter. I mean, between the shenanigans of Zeus, one of Poseidon’s brothers, who rapes both divine and mortal women left and right, and Hades, who kidnapped a woman and conned her into staying with him even after agreements were made for her to return home, should it really be any surprise that their trident-sporting sibling would be no better?

However, there were a few early 20th century scholars who interpreted the myth of Medusa and Perseus as a memory of actual invasion that turned into a myth.

The legend of Perseus beheading Medusa means, specifically, that “the Hellenes overran the goddess’s chief shrines” and “stripped her priestesses of their Gorgon masks”, the latter being apotropaic faces worn to frighten away the profane.

That is to say, there occurred in the early thirteenth century B.C. an actual historic rupture, a sort of sociological trauma, which has been registered in this myth, much as what Freud terms the latent content of a neurosis is registered in the manifest content of a dream: Registered yet hidden, registered in the unconscious yet unknown or misconstrued by the conscious mind.

J. Campbell (1968)

Some of the myths detail Perseus displaying Medusa’s head on the bow of his ship to petrify his enemies, but if you follow Campbell’s reasoning, this might also be a metaphorical way to describe how his victory and treatment of the defeated terrified his later opponents to much that they chose to surrender and hope for mercy, rather than fight back.

I heard one story, so long ago I can’t remember the events surrounding it, but it was at a pagan event. I was in a rather large group discussion on how the whole concept of “the winner is the one who gets to write history” applies to mythology, folklore, and spirituality as well. And one of the people present brought up Medusa, and how she may have been a high priestess, and the snakes on her head symbolised the priestesses she was responsible for.

It made sense to me at the time, and now, thinking of the above interpretation by Campbell, it clicks even more. How often have we, in our dragon discussions on the Mythsterhood, come across dragons that have gotten demonised in an attempt to discredit the beliefs and ways of life that go hand in hand with them?

But yet again, Medusa is a topic I could go on and on about, so best get moving.

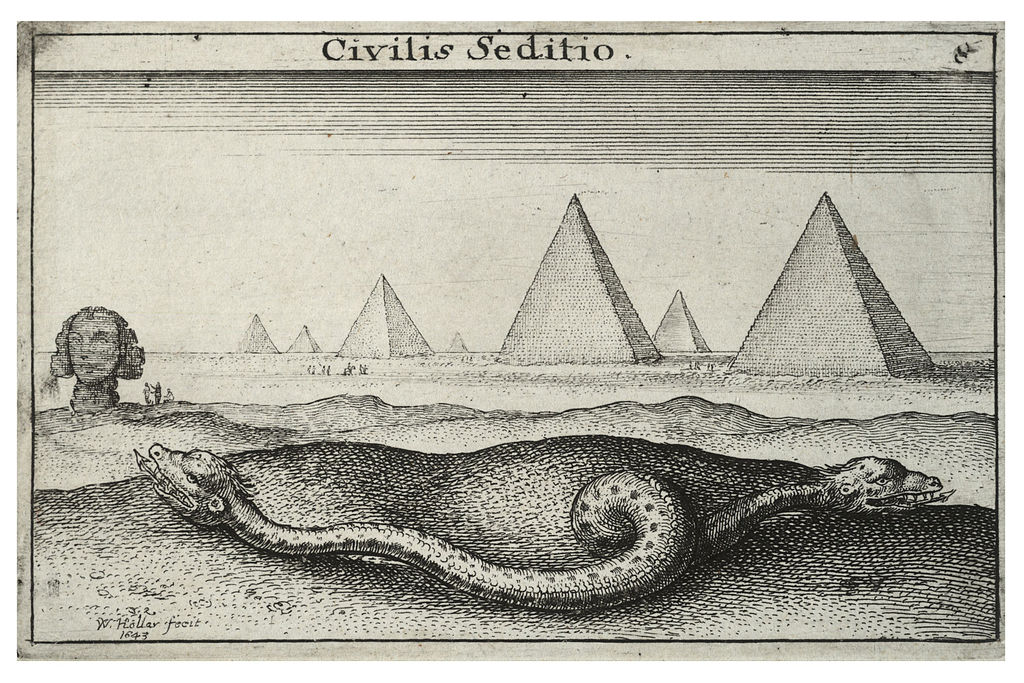

Amphisbaena

Staying in Libya, this region is home to another fascinating dragon. The Amphisbaena or Mother of Ants was a venomous serpent with a head at each end, and a diet consisting mostly of ants.

While later (medieval) sources depict her with two or more scaled feet, particularly chicken feet, and feathered wings, sometimes even horned and with small ears, she definitely starts out her career very much as a “plain” double-ended serpent.

While this means she’s not as extraordinary a hybrid as the Chimera, of course, she does certainly have a place here.

Guess how she came to exist? When Perseus flew over the Libyan desert, on the winged sandals acquired from the Graiae–side note: since Hermes and Athena helped him get some leverage on the Graiae, perhaps this is how Hermes originally got his feathered footwear?–blood dripped from Medusa’s severed head and landed in the sand. The amphisbaena spawned from those drops of blood.

Despite the dangers posed by proximity to the Amphisbaena, she was rather popular in folk medicine. In these sources, it seems like the creature is almost considered a species, rather than a singular monster. Or perhaps the original Amphisbaena reproduced and her progeny was named after her.

At any rate, according to Pliny, pregnant women could wear a live specimen around their necks to assure a safe pregnancy. For some reason, a creature whose own mother was treated so horribly which then goes on to protect other mothers feels oddly satisfying to me.

However, and to the detriment of the amphisbaena themselves, if you were not pregnant but just suffering a bout of arthritis or a common cold, you should wear only its skin. And as a bonus, eating the meat would attract many lovers.

Let’s move to yet another monster that, although the term monster is again, depends on how one defines a monster.

Ophiotaurus

Let’s end on one final creature that–through no doing of its own–drew the wrong kind of attention from the Greek gods.

Ophiotaurus is a tricky beastie to track down, but I managed to find a few tidbits.

The creature had the head, front legs and torso of a black bull, and the tail of a serpent. He was one of the children of Gaia, though some sources describe him as one of the creatures that came out of chaos alongside Gaia and Ouranos.

While Ophiotaurus did not choose a side in the conflict between gods and titans, the Fates made a rather unfortunate prophecy at the time of the creature’s birth. If someone were to slay it and burn its entrails, it would ensure victory against the gods.

Hence their desire to make certain no one got their hands on the unfortunate hybrid. The goddess Styx, personified in one of the rivers running through the underworld, imprisoned him in a walled grove. However, Aigaion, a giant and ally of the titans, found the Ophiotaurus and got to work right away, killing and butchering it.

Alas, before he could get the fire going, Zeus sent birds of prey–sources vary as to the type of bird, from kites to eagles, as well as the number–to steal the innards.

Zeus placed the Ophiotaurus in the sky as the constellation Taurus, which to this day is still sometimes depicted as a bull-serpent hybrid. It’s a nice change to see the Greek gods as not being the aggressors here. While they did imprison the creature, they could have easily killed it themselves and disposed of the creature’s entrails in a safe way so as to permanently eliminate the risk of someone performing the ritual that would guarantee their demise.

Only one extant mention in writing can still be found of the Ophiotaurus, in Ovid’s Fasti, though the story may have had a more important role in the Titanomachia, a lost Greek epic detailing the war between titans and gods.

So, let’s end on a somewhat positive note: perhaps the Greek gods weren’t shitheads all the time. Still, if this wasn’t clear just yet, I’m on the side of the monsters, mostly.

Until next time,

Later Mythsters!

Sources

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chimera_(genetics)

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chimera_(mythology)

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lycia

- https://www.britannica.com/topic/Chimera-Greek-mythology

- Schmitt, Marilyn Low. “Bellerophon and the Chimaera in Archaic Greek Art.” American Journal of Archaeology, vol. 70, no. 4, 1966, pp. 341–347. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/502324. Accessed 27 Mar. 2021.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gorgon#cite_ref-Campbell1968_10-0

- Campbell, Joseph (1968). Occidental Mythology. The Masks of God. 3. Penguin Books. pp. 152–153. ISBN 978-0140194418.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Metamorphoses

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Medusa_(Bernini)

- Ovid, Metamorphoses, Books I-VII

- https://www.britannica.com/topic/Perseus-Greek-mythologyhttps://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Amphisbaena

- https://www.theoi.com/Thaumasios/Amphisbainai.html

- Hidden from View: the Medusa Myth fromOvid’s Metamorphoses to Peter Paul Rubens

- https://monster.fandom.com/wiki/Ophiotaurus

- https://www.theoi.com/Ther/TaurosOphis.html

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ophiotaurus#:~:text=In%20Greek%20mythology%2C%20the%20Ophiotaurus,part%20bull%20and%20part%20serpent.

- Images: Wikimedia Commons

Jasmine Arch

Jaz, also known as the Wolf Mother, is a writer, poet, narrator, and vessel of chaos. She is eternally grateful for her mother’s refusal to curtail her children in their choices–whether that was literature, spirituality, studies, or appearance–and grew up devouring her older brother’s collection of fantasy novels. In hindsight, telling stories of her own seems inevitable, but it took her a while to accept this and find the courage to begin.

Be First to Comment